Moving Between Nature

2021

Eduardo Serrano

Margarita Lozano is considered one of the most consistent artists in Colombia’s artistic scene. Over the last seven decades, her work has remained loyal not only to its themes, but also, and, in particular, to its definitions and values. The same conviction which encouraged her childhood explorations, the same creative motivation which drove her from an early age, to seek, using her pencils and brushes, the expression of her appreciations about the world and the same desire to produce aesthetic pleasure, have remained as immovable pillars of her art work, granting her work a type of cohesion and unity, which are difficult to match in the national artistic panorama.

Margarita Lozano is considered one of the most consistent artists in Colombia’s artistic scene. Over the last seven decades, her work has remained loyal not only to its themes, but also, and, in particular, to its definitions and values. The same conviction which encouraged her childhood explorations, the same creative motivation which drove her from an early age, to seek, using her pencils and brushes, the expression of her appreciations about the world and the same desire to produce aesthetic pleasure, have remained as immovable pillars of her art work, granting her work a type of cohesion and unity, which are difficult to match in the national artistic panorama.

This, however, does not imply that Margarita Lozano’s work has remained static during seventy years, nor that differences do not exist between pieces of one period and another, or even between canvases of the same period. On the contrary, each of her pieces, despite emerging from the historical principles which have guided her production, accumulate a succession of considerations and of thematic, chromatic, formal, emotional and sentimental reflections, which contribute to the production of original, unique and independent images.

Her work has seen a clear evolution over the years. This is made evident when viewing her first pieces, carefully depicted, but without boasting experimental techniques, the orientation, gestures and spontaneity of her later work, also in the way she subsequently alters reality, likewise in the use of color and her clear admiration for the world’s maestros during the different periods of the History of Art.

We must not forget that the artist was born in Paris during the time when artistic movements were being established after the impressionist movement, and that Paris, due to those movements, had become the art capital of the world. Two decades later, Margarita Lozano familiarized herself with art and, in particular, with painting. In Paris and later, in Rome, she had the opportunity to directly appreciate the work of great masters, as well as being able to attend prestigious academies in which she learnt about different techniques, used in artistic representations during the mid 20th century.

No doubt, this being the main reason why, as we appreciate Margarita Lozano’s work, memories and associations are triggered among art connoisseurs, which, although none are quite connected, none are identifiable with previous work, none specifically close to the work of other artists, nonetheless, allow us to evoke, because of their spirit and character, those moments in which modernism began, the great height of painting, of important and moving artistic expressions and of an intense historical creativity, which has remained to date, as one of the most fascinating periods of the History of Art.

Without a doubt, Margarita Lozano has been a privileged artist, who was able to witness, value and admire, not only through books and reproductions, (when, at the time, this alternative did not exist for Latin American artists who were so far removed from the History of Art between the early colonial times until the middle of the 20th Century) some of the major changes which were happening in the advent of painting. The artist lived through the artistic transformations of the first half of the 20th Century. However, that privilege, instead of it being a merit in Colombia for having assimilated and having introduced new approaches of modernism, was poorly regarded by the art critics at the time who did not consider it valid for a young woman from Bogota’s society to be interested in art.

It is clear that the young artist did not choose the social strata into which she was born; one which surrounded her with affection and the support of family members, who, undoubtedly contributed to instilling the necessary confidence which led her to becoming an artist. What Margarita Lozano was able to choose for herself, within the broad spectrum of possibilities which emerged for painting during the middle of the 20th Century, and which she chose decisively and with clarity, were the chromatic, formal and compositional objects which distinguish her work, conferring upon her a distinctive nature and identity.

Amongst the possibilities which opened up for artists during that period and which appealed enormously to Margarita Lozano include: the interest in Nabis painters (for their domestic themes and the subtle deformations of reality they painted as a result of the emotions which these subjects represented), the provocative use of color which Fauve artists adopted and the dedication to three main themes: still life, portraits and landscapes.

For all of the above reasons, one could claim that Margarita Lozano’s work introduced in Colombia important aspects of the different movements which had emerged and which followed the creative purposes initiated by the impressionists, made known in Colombia through the work of Andrés de Santa María. However, Margarita Lozano’s work is closer to expressionism, not so much in the sense of its gestures, which generally are associated with this movement, but in the sense of altering reality to imbue its representations with its distinguishing sentiments and emotions towards nature.

The aspect of Margarita Lozano’s work which is most known and debated by art commentators has been her still lifes. This is evident as a large part of her work is focused on the representation of fruits, vegetables, cutlery and other inanimate objects which are placed on tables, as well as different types of everyday furniture. The majority of her still lifes, just as the majority of her paintings, are depicted in interior atmospheres and, although some are depicted in non-specific and generic surroundings, with undecipherable luminous backgrounds, others, on the other hand, are easy to decipher due to the carpets, paintings, libraries, mirrors and other objects which are found in her home.

The aspect of Margarita Lozano’s work which is most known and debated by art commentators has been her still lifes. This is evident as a large part of her work is focused on the representation of fruits, vegetables, cutlery and other inanimate objects which are placed on tables, as well as different types of everyday furniture. The majority of her still lifes, just as the majority of her paintings, are depicted in interior atmospheres and, although some are depicted in non-specific and generic surroundings, with undecipherable luminous backgrounds, others, on the other hand, are easy to decipher due to the carpets, paintings, libraries, mirrors and other objects which are found in her home.

The elements used in her still lifes are carefully arranged and organized in a manner in which there is no visual interference, or if there is interference, nonetheless, allows them to be identified due to the segments which remain visible. Her images, although include similar elements (which one may think may lead to repetition), are infinitively different, demonstrating her imagination, her resourcefulness with compositions and most of all, her main interest in light and color.

Light plays with the brightness and firmness of the fruit and with the flower arrangements, and, interestingly enough, like in Fernando Botero’s still lifes, light does not project shadows, or if it does, it is not very defined in a way that it does not interfere, neither with the radiance of some of the images, nor with the sobriety of others. This could apply to the artist’s different emotional states and of course to the colorful subjects.

Margarita Lozano’s still lifes, both of flowers and fruits, often combine different species giving them a wonderful mix of color and illumination. Sometimes she paints still lifes using just one type of specimen, or type of vegetable or other food, such as eggs, usually arranged in baskets and accompanied by objects such as clocks, jars and other elegant pieces of tableware.

Margarita Lozano’s frequent use of clocks in her work could be interpreted as a reference to the passing of time. As early as the 16th Century, the use of clocks in still lifes was a reminder of the course of time and were frequently used in paintings of vanitas, which were representations about the inevitability of death. There are some interesting examples of these in Colombia. However, in Margarita Lozano’s case, the use of clocks has a different meaning. The clocks used are clearly antiques, like many other of the objects she uses to accompany flowers and fruit, all of them reflecting, in a relatively eloquent manner, her lifestyle, taste and personality.

Not all of her still lifes are bright, some are sullen and nostalgic, reflecting the melancholic light of Bogota’s savannah, given the harmonic synthesis of their colors. In these paintings, it is more evident to sense, the dreamlike and idealistic atmospheres, which are actually present in all of her work. Some of her work is painted in black and white, being not only a reflection of her mood and of her emotions, but also suggesting an artistic challenge – to forego color and communicate by drawing, her shapes and outlines, her aesthetic creed.

Margarita Lozano’s still lifes convey a great sense of peace, without implying that they do not reflect profound emotions, but, rather, that she dominates these emotions and depicts them on to a canvas. In many of her canvases, the objects and food engage in an interesting and colorful dialogue with a contrast coming from the design of carpets and wallpaper.

Her art also transmits a certain sense of solitude, but not an imposed or tormented solitude, but rather a peaceful and calm solitude, which allows her to concentrate. The artist has said that she paints “her own, solitary world”, which suggests that this solitude plays an important role in the creative process and that her painting, although reflecting the outside world, emerges out of her innermost self and which responds to her thoughts and perceptions. Her independence and privacy are fundamental to this creative process.

In the same intimate way, she looks at her surroundings, Margarita Lozano has developed a series of portraits, which, like her still lifes, were produced during her different periods, although to a lesser extent. The majority of her portraits are mostly of indigenous or black children, as if wanting to express that all of humanity share the same type of emotions. As if reflecting the age of innocence, almost all of the children appear with their First Communion outfits and dresses.

In these compositions, as in her still lifes, the layout of her subjects and everything that surround them are very expressive. The figures are not always in the center, but rather, frequently appear to one side giving way to flowers and other elements which usually accompany them. The children she paints are not smiling but rather, are poised as sensible, prudent children who are looking ahead, as if alluding to that childhood curiosity and desire of getting to understand the world.

It is interesting to point out, that nature appears in the majority of her portraits. Flowers usually accompany her figures, emphasizing the artist’s devotion and fondness of nature, plants and gardens, all of which express her own feelings and appreciations about her childhood, life and the world. It is important to stress, at this point, that the artist applies with the same skill, the use of oils and pastels, and that the majority of these compositions, as well as a large number of her themes, have been accomplished using pastel, giving her work a certain radiance, which seems alive and soft. Pastel was a favorite medium for some of the impressionists, but also for the Nabis painters and especially for Vuillard.

Her close connection with nature is evident in many of her paintings of interiors, in which the artist, despite not painting the open air and sunlight, is able to convey her love of nature by depicting flowers and fruit. In these pieces of art, the artist’s joy in depicting the shape and color of objects is evident, with their proportions, their location within space and their inter relation. It is not surprising that Bonnard is mentioned as a reference when appreciating her work. joie de vivreis very much present in Margarita Lozano’s art.

Her close connection with nature is evident in many of her paintings of interiors, in which the artist, despite not painting the open air and sunlight, is able to convey her love of nature by depicting flowers and fruit. In these pieces of art, the artist’s joy in depicting the shape and color of objects is evident, with their proportions, their location within space and their inter relation. It is not surprising that Bonnard is mentioned as a reference when appreciating her work. joie de vivreis very much present in Margarita Lozano’s art.

Her art also conjures up the intimate character of Vuillard, one of the Nabis painters, who also painted interiors and who also had an inclination of painting everyday life, as well as the tendency to include figures, like, in Margarita Lozano’s case, a boy playing the piano or a girl eating.

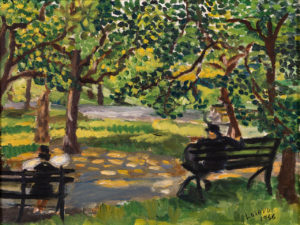

Margarita Lozano’s predilection for depicting nature include her landscapes which compliment that devotion towards nature in all of its forms and which has been guiding theme throughout her art and throughout this text.

Margarita Lozano’s predilection for depicting nature include her landscapes which compliment that devotion towards nature in all of its forms and which has been guiding theme throughout her art and throughout this text.

Nature, present in all of Margarita Lozano’s periods, has little connection to her Colombian predecessors, those artists grouped together in the Escuela de la Sabana. It is worth recalling that although sporadic representations of the Colombian landscape were produced from the colonial period onwards, it is true to say that landscape art as such, in the full sense of its definition, had its origins in Colombia in 1894 with the creation of the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Bogota and where painters, such as Andrés de Santa Maria and Luis de Llanos, were conscious that, during the 19th Century, landscapes had reached the greatest height in the hierarchy of artistic themes.

For example, the influence of the Barbizon School is evident in the work of Luis de Llanos, while impressionism is present in that of Andrés de Santa Maria’s work. Later on, there was also a synergy with expressionism, which included the Fauves artists, like Margarita Lozano, but using raw materials and developed after returning from Europe. One could argue that landscape painting emerged in Colombia as a result of the combination of two contradictory artistic concepts, both with a French origin.

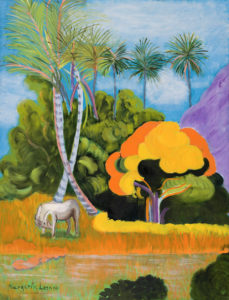

Margarita Lozano’s work has roots in French painting and could be called “romantic modernism”, due to the fact that her paintings are frequently tinged with a certain poetic idealism. As with her still lifes, her use of color imposes a sense of character into her depiction of living nature. In other words, Margarita Lozano does not seek to reproduce still lifes, nor landscapes, or figures in a realist manner, but rather reproduces the sentiment that these subjects portray in the face of nature.

Artists from the Escuela de la Sabana and Margarita Lozano share, although in different ways, their admiration for the plateau of Cundinamarca and Boyacá. The former liked to find nooks and crannies, rocks and rivers, views and their privileged location from the Andean ridges, the latter was more interested the light of the savannah, its vegetation, gardens and flowers and its dim and subtle atmosphere.

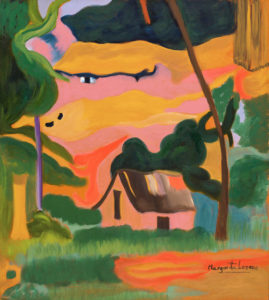

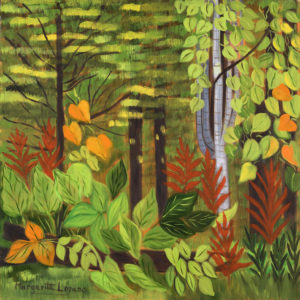

Margarita Lozano’s art also depicts landscapes and vegetation in warmer climes such as Nocaima, a small mountainous town, outside Bogota, with a warm and humid climate and fertile soil which gives way to lush vegetation growing between ponds and streams, intertwining with native flora and tropical plants. The variety of ferns and especially flowers, which stand out due to their colors, the achiote plant (Bixa Orellana) with its clusters of spiked red pods, are the ones which the artist frequently includes in her still lifes, and celebrate the attractiveness of this region.

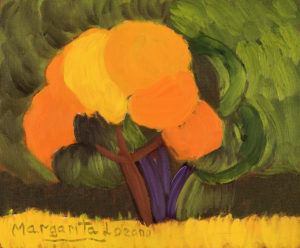

If it is somewhere the artist expresses her freedom, it is in her landscapes, where sometimes, for example, she paints mountains using pinks and lilacs, or uses red to paint trees, where plants take on unscientific hues but achievable through the artist’s imagination, allowing the observer to transport him/herself to the artist’s dreamlike and poetic world.

If it is somewhere the artist expresses her freedom, it is in her landscapes, where sometimes, for example, she paints mountains using pinks and lilacs, or uses red to paint trees, where plants take on unscientific hues but achievable through the artist’s imagination, allowing the observer to transport him/herself to the artist’s dreamlike and poetic world.

It is then, when the observer has reached the heart of Margarita Lozano’s work and can fully enjoy her art, because it is now that one does not necessarily seek to find representations of reality, like documented pieces about the planet, but rather as evidence of the artist’s capacity to create wonderful worlds where truth is subjective and is measured by the fidelity towards an idea, rather than exact coincidences with the visible world.

Like Matisse, Margarita Lozano could say “When I paint green, it is not always grass; when I paint blue, it is not always the sky. Drawing gives composition, color gives the sensation”. Also, if one considers the expressive use of color, the fluidity of her drawing, as well as her intention to portray tranquility, harmony and serenity, it is evident that Matisse, the Fauve artists’ most outstanding figure, is a major conceptual reference in Margarita Lozano’s work.

Although the way in which she uses colors can be seen as risky, in most cases they are interpretations or an intense use of natural colors. Yellows are always more intense, greens are glossier and reds shinier. From a formal point of view, it is clear that the artist paints in situ, surrounded nature. It is evident that she omits the details of plants and freely alters the vicinity between them.

Paradoxically, it is precisely the freedom in her use of color and nature’s changing character, that gives her work a sense of contemporaneity. The observer, like with David Hockney’s art, views the pieces with an unprejudiced manner, where tones and hues are sometime imaginary and not strictly reflecting reality of like Daniel Heidkamp’s art, which registers the history of the plant world from determined places with a coloring of Fauve influence.

Works of art are representative of contemporary landscape painting. We must not forget that this form of art has been present in different periods, or at least since the 16th Century, standing as a testimony, of the changing aspects of nature as well as a testimony to the changing artistic considerations towards painting. Margarita Lozano’s art, as well as that of the aforementioned masters, show nature, not only as a source of inspiration for painters but also as a source of enjoyment, which can be appreciated through painting, as a direct experience from nature itself. One could argue that, as a result, and due to her perseverance, her art has taken on a new lease of life.

Her relative realism emanates from her perception about spaces, objects and events which form a conscious impression of physical reality and its surroundings. From this point of view, her art seems to argue that there is a great pleasure in the search of beauty and in the admiration for the simple joys of life. The evolution of Margarita Lozano’s takes place within her own parameters and her drive is in the search of excellence in the expression of her own definition of Art.

Her paintings of exteriors are not large panoramic views, rather isolated spaces, in which the horizon is not clear and where each tree, plant and flower takes on a main role. In the majority of these paintings, each element is placed carefully, like in her still lifes, in other words, there is no visual obstruction between each object.

Her paintings of exteriors are not large panoramic views, rather isolated spaces, in which the horizon is not clear and where each tree, plant and flower takes on a main role. In the majority of these paintings, each element is placed carefully, like in her still lifes, in other words, there is no visual obstruction between each object.

In her work, there is evidence of elevated spaces, where trees are painted, with their vigorous and strong foliage, testimonies of the power of nature. However, in the majority of her art, the height of her paintings has a limit, and the totality of say, bamboos are seldom seen. Only fragments of bamboos, which can measure up to 20 meters, alongside leaves and flowers, occupy the front parts of the paintings.

In some of her paintings, plantain leaves (musa paradisiaca) and a variety of palm trees from different countries, stand out or ramble out from the low vegetation. The overall result looks like a cascade of leaves and flowers, giving a wonderful fresh visual effect, a certain Baroque style, a patchwork effect, as well as a sense of the heat and humidity, characteristic of tropical climates.

Her Baroque style, brings her work closer to Colonial paintings, where a certain spiritual reaction is sought after. Her paintings of the natural world are an exaltation of nature, which lead to profound thoughts about our wellbeing and about our planet.

Many of these landscapes are reflections of her own gardens and particularly gardens grown by her late husband, Enrique Cavelier. Aware of her devotion towards nature, he ensured she was surrounded by trees and plants. The way in which he laid out his gardens, sometimes brings to mind Monet’s gardens in Giverny and Van Gogh’s gardens in the hospital at Arles.

It is evident that Margarita Lozano’s work is perfectly tuned in with chapters of the History of Art and is clearly receptive towards certain values and characteristics of the different periods. However, it is also clear that the artist was never inclined towards avant-garde movements like cubism, constructivism, pop or hyper-realism, unlike a number of Colombian artists who followed aspects of these movements.

As avant-garde art is currently considered obsolete, when landmark movements are non-existent, the values emanating from Margarita Lozano’s work can be appreciated in a more neutral manner, with less dependency on market opinions or styles. Her personality and the individuality towards her work clearly emerges, allowing us to appreciate the fruits of her isolation from conceptual trends and opinions, which at times suppress the individual, the individual being the source and recipient of works of art.